A Post-Residency Seal Carving Exhibition

This is a special year for Singapore and Malaysia as we mark 50 years of bilateral relations. In addition to our economic and social ties, our various cultural exchanges over the years have been helping to strengthen the friendship between our countries.

The opening of Singapore-Malaysia Cross Cultural Exchange: A post-residency seal carving exhibition is yet another milestone in our cultural ties. Since 2009, Temenggong has been creating opportunities for artists to learn from one another. In March 2014, it organized a seal-carving residency where seal carvers from Singapore and Malaysia came together and created more than 100 pieces of seals. Three Malaysian seal carvers – Chong Choy, Tai Boon Piow and Tan Shin Tiong – who were artists-in-residence at Temenggong were joined by three Singaporean seal carvers – Oh Chai Hoo, Soo Suan Cheok and Tang Yip Seng. Through their creative collaboration, they produced a range of seals out of stone, wood and porcelain.

All their works will be displayed in this exhibition where visitors can appreciate the fine craftsmanship from our two countries. Beyond this exhibition, there will also be two workshops on seal carving so that more Singaporeans can have a chance to try the art of seal carving.

I would like to thank Temenggong for successfully bringing our artists together, and sharing their works with Singaporeans through the exhibition. It is significant that it happens during the year when we mark our 50 years of bilateral ties. It is special too for Singapore, as we are celebrating our Golden Jubilee year. I hope that Temenggong will continue to have more of such exchanges for the artists between Singapore and Malaysia, and help to strengthen the ties our countries share.

— Mr Sam Tan

Minister of State

Prime Minister’s Office &

Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth

New Impressions:

A Post-residency Exhibition on the Art of Seal Carving

It may be useful, against the context of this exhibition of contemporary seal carving, to remind ourselves that the seal is an object common across several civilisations for being the symbol of identity and authority: Clay seals are found as far and wide in archaeological excavations from the Mesopotamian and Indus Valley Civilisations, and before bronze seals were used as official, courtly implements in China, seals made of clay were also made. The terms “signet ring”, “insignia” are linguistic legacies of these objects. Seals are used for official and private purposes, and speak for the integrity of the document marked, for trade, for privacy, or to convey the weight and purport of the owner of the seal. They are the earliest forms of the contemporary logo, or brand (words which themselves carry association to the idea of an imprinted image). Seals may be distinguished into two general classes, official seals, used to endorse official documents, or private, personal seals, created and used for enjoyment. So important were seals for official business, that it was common practice to destroy official seals upon the death of the user, to prevent forgery. Conversely, there appears to be a larger remnant body of personal seals created for pleasure, which become collectors’ items.

While seal marks may appear to be flat and two-dimensional, the creation of these imprints is conceptualised and finalised in three-dimensions. The calligraphic imprint is first imaged, created, and inversed; lightly inked marks may transfer onto the paper and be taken into the fibres without leaving any traces; but a thicker application of seal-wax leaves behind a caked aspect that reminds the viewer of the materiality of the seal. More than anything else, the employment of a stone or wood as the material to be carved on, confers onto seals their obvious three-dimensionality. Early functional seals dating to around the Han Dynasty period (206BCE-220CE) had knobs or rings, presumably allowing them to be worn, but by the time of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), the decoration on the body of seals became increasingly important. The individuality of seals extended beyond the names of the owner or the calligraphic styles of the seal carver, to be seen in the transformation of seals into sculptural objects.

In the context of Chinese art, private seals are commonly associated with the “scholarly arts” of calligraphy and art, and scholar gentlemen collected seals as connoisseurs. The art of seal carving was a way of exchanging a common appreciation of the knowledge and execution of ancient scripts among friends. It is not uncommon for scholar-artists to design and create a seal, often for another. In keeping with the association of seals and the identity of their owner, seals are often used as one of the means to authenticate paintings, either by way of identifying the artist, or establishing provenance through the collector’s seal. What may be lesser-known or remembered in our time is that apart from name seals, another class of personal seals was the xianzhang (闲章;”leisurely” seals), with many different variations in the motifs carved onto seals, not just in the style of seal scripts employed, but also in the diversity of imagery and phrases that may be adopted.

The current exhibition is the fruit of a residency undertaken by six artists from Malaysia and Singapore at Visual Arts at Temenggong in March, and brings about several of these elements of traditional seal-carving touched on above: the residency was conceived for artists from both sides of the Singapore-Malaysia Causeway to exchange their ideas and elements of their respective media and practice. For historical and political reasons, the classical arts in this area once remembered as the Nanyang (Southern Seas) developed a trajectory away from changes in the Mainland since the 1950s, yet retaining always at its core a traditional racine. Nonetheless, the discussion above of the history of seal carving would be fundamental to each of our artists, who identify their practice as deriving its gravity from tradition.

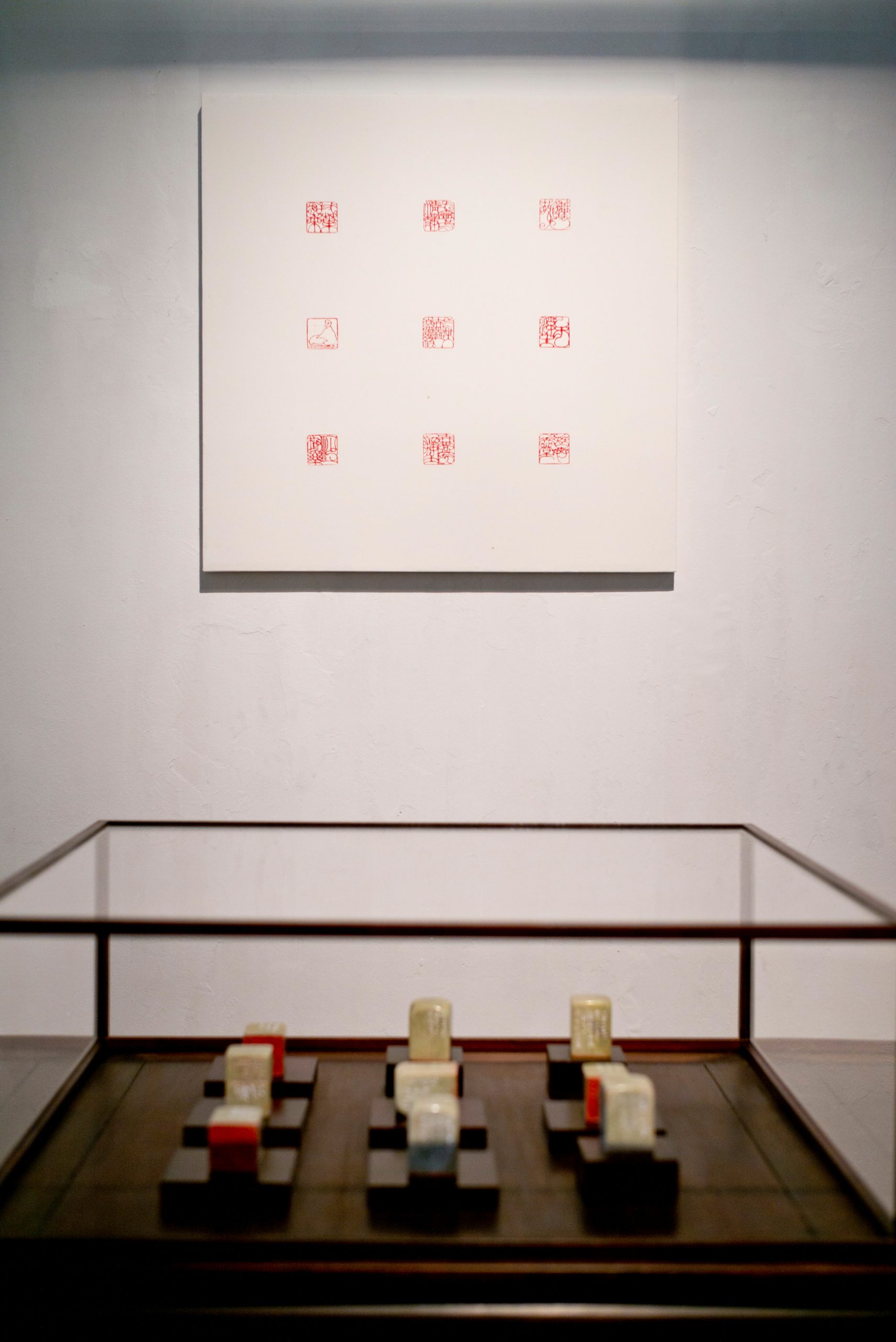

The works featured in this exhibition do not convey identity in the sense of the conventional use of the seal. The xianzhang on display primarily reflect the personalities of the artists who have created them, as the opening display presents. The works reveal the strengths of each of our artists’ practice: those who more frequently practice classical calligraphies and painting reveal this tendency in their creations; others who tend towards design and abstraction utilise their methods to different outcomes. Our six artists have departed from the utilitarian function of the seals to celebrate the myriad artistic and creative possibilities afforded by the medium, the variety of seal scripts and the combination of “positive” and “negative” impressions (朱、白文). The carved imprints are naturally important to the exhibition, but the element that will capture the audience’s immediate attention will be the sculptural forms the seals take.

Stones are some of the most identifiable media immediately associated with seal-carving, and they may be purchased in the form of polished blocks ready to be carved and sculpted, as seen in the regular pieces used by Tang Yip Seng and Tai Boon Piow. Carvers usually favour “soft” stones from mainland China (such as from Shoushan or Shuikeng), but these have become more expensive in recent years. A suitable alternative was found by ours artists in stones from Batu Kluang in Malaysia (南山石), and this stone was responsive to the carver’s knife, and had a good colour and lustre when polished. In this exhibition our artists have tended to allow quality stones to stand out without overly embellishing them, allowing the calligraphic elements of the seals to be the central feature. The viewer is invited to focus on the artist’s calligraphy in both the carved seal imprint, as well as the side inscription (边款). Far from being plain and bare, Tang and Tai break free from the regular structure of prepared stones with calligraphy, inscriptions and illustrations in the xieyi spirit (写意; loosely translated as “free expression”). Soh Suan Cheok (whose name in Chinese 宣石 may be taken to mean “acclaiming the stone”) and Chong Choy play with the natural shapes and qualities of stones freely, allowing the geological beauty of the stones to be the main decoration, at times letting the stone set the inspiration of the motif (as seen in Chong’s ‘frog’ seal.) Generally, the aphorisms carved into the seal are phrases in keeping with environmental simplicity, sometimes expressed in the fauna-inspired bird-and-worm style of seal script (鸟虫纂).

Materially, in addition to stone seals, the exhibition engages with objects traditionally used in seal carving – wood and clay – before soft stones became more popular from around the 13th century onwards. Stones, both of Chinese and Malaysian sources, are becoming heavily mined to supply seal-carvers (which is an indication that the craft is alive, if not experiencing a resurgence of interest.) There are signs of environmental damage arising from extensive mining. In this context, the ceramic seals of Oh Chai Hoo and the wood-carved seals of Tang Yip Seng and Tan Shin Tiong appear to be timely in proposing an update to the ceramic and wood media for seal-carving, before contemporary concerns about environmental sustainability become manifest. Moving away from the standard cuboid forms of early clay seals, and revealing a tendency towards abstraction and familiarity of international studio pottery techniques and glazes, Oh transforms the humble format into patisserie-inspired forms, including the kueh lapis. Soh also has ceramic seals in his repertoire, created during the residency, shaped like stones, with carved natural motifs inspired by the environments of the Temenggong estate. As a variation to the Tang’s wooden seals that are reminiscent of scholarly accessories in their design, Tan primarily uses found or salvaged wooden objects such as chair parts, nonya pastry moulds, or tree branches as the medium for his carvings. The metallic and raku-glazed shininess of Oh’s seals paired with Tan’s rings makes a play on contemporary aspirations to all that glitters: yet the seal impression reveals proverbs, reminiscent of Daoist naturalism, and Buddhist images respectively, providing subtle cautions against material ostentation.

The description of seals in the earlier paragraphs may have appeared to set these ‘scholarly objects’ up in the mythicised realm of an idyllic past, with little relevance to the present. This would have been the case, if we consider that seals should be confined to the classical scholarly arts in the way some people think the related art forms of Chinese ink and calligraphy should be categorised as guohua only, an art form imbued with ‘national’ character, belonging only to the Chinese culture and no other, with mainly historic, and little contemporary, relevance. Should this be true, should there be no relevance of seals to the present, this category of things have very little other place in our lives today, other than to be consigned to museum vitrines. Yet, the artists of this residency and exhibition have found a way to reinvent their ink and calligraphy practice into the contemporary through their seals, at times interacting with other artistic concepts from international styles and movements to create new forms. As ink and calligraphy develop and broaden beyond their classical and scholastic associations, finding new ways to provide artistic pleasure, so too, can seal carving find new means of expressions.

— Chang Yueh Siang

Curator, Lee Kong Chian Collection of Chinese Art

NUS Museum