Longings / 寄望 / Jiwa

Longings / 寄望 / Jiwa

Boedi Widjaja

Fyerool Darma

“2019 is a special year for Singapore as we commemorate our Bicentennial. Longings/寄望/jiwa could not have come at a more fitting time as we reflect on our past, as well as our hopes for the future. Organised by Temenggong Artists-In-Residence, in partnership with the National Museum of Singapore (NMS), the exhibition features the work of two young Singaporean artists, Fyerool Darma and Boedi Widjaja.

Through their art, we have the opportunity to look back on our Singapore Story to appreciate the values that have brought us where we are today, and consider how we can move forward with confidence.

For this exhibition, the artists drew inspiration from the Tang Holdings Raffles Collection, comprising memorabilia and over 120 letters written by Sir Stamford Raffles.

I would like to thank Mr Tang Wee Kit for donating the Tang Holdings Raffles Collection to NMS.

For the past 10 years, Temenggong Artists-In-Residence has been providing platforms for local artists and promoting visual art to Singaporeans. Here’s to many more years of supporting our artists—happy 10th anniversary to Temenggong!”

Ms Sim Ann

Senior Minister of State

Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth &

Ministry of Communications and Information

Longings / 寄望 / Jiwa

0.

Our project begins with the space: a residency atop a hill facing the Malay sea. The address, Temenggong Road, makes reference to historical events between 1819/24 that relocated the Temenggong’s residence to Telok Blangah. Looking out, before Harbourfront and Vivocity were built, we would have seen the Straits; the islands of Sumatra and Java lie beyond, placing Singapore within the context of a Malay world. It is a regional and geographical context that Raffles himself understood himself to be in (after all: Raffles himself had been Governor of Java between 1811 – 1816), which we may easily overlook today:

“Situated at the very extremity of the [Malayan] Peninsula, all Vessels to and from China via Malacca are obliged to pass within five miles of [Singapore] … the run between these Islands and the Carimons, which are in sight from it, can be effected in a few hours, and crosses the route from which all Vessels from the Northward must necessarily pursue which are bound towards Batavia and the Eastern Islands …”[i]

[i] Raffles, “Account of the Founding of Singapore”, despatch to the Supreme Government in Calcutta, 13 February 1819 (Facsimile donated to National Museum May 2019)

1.

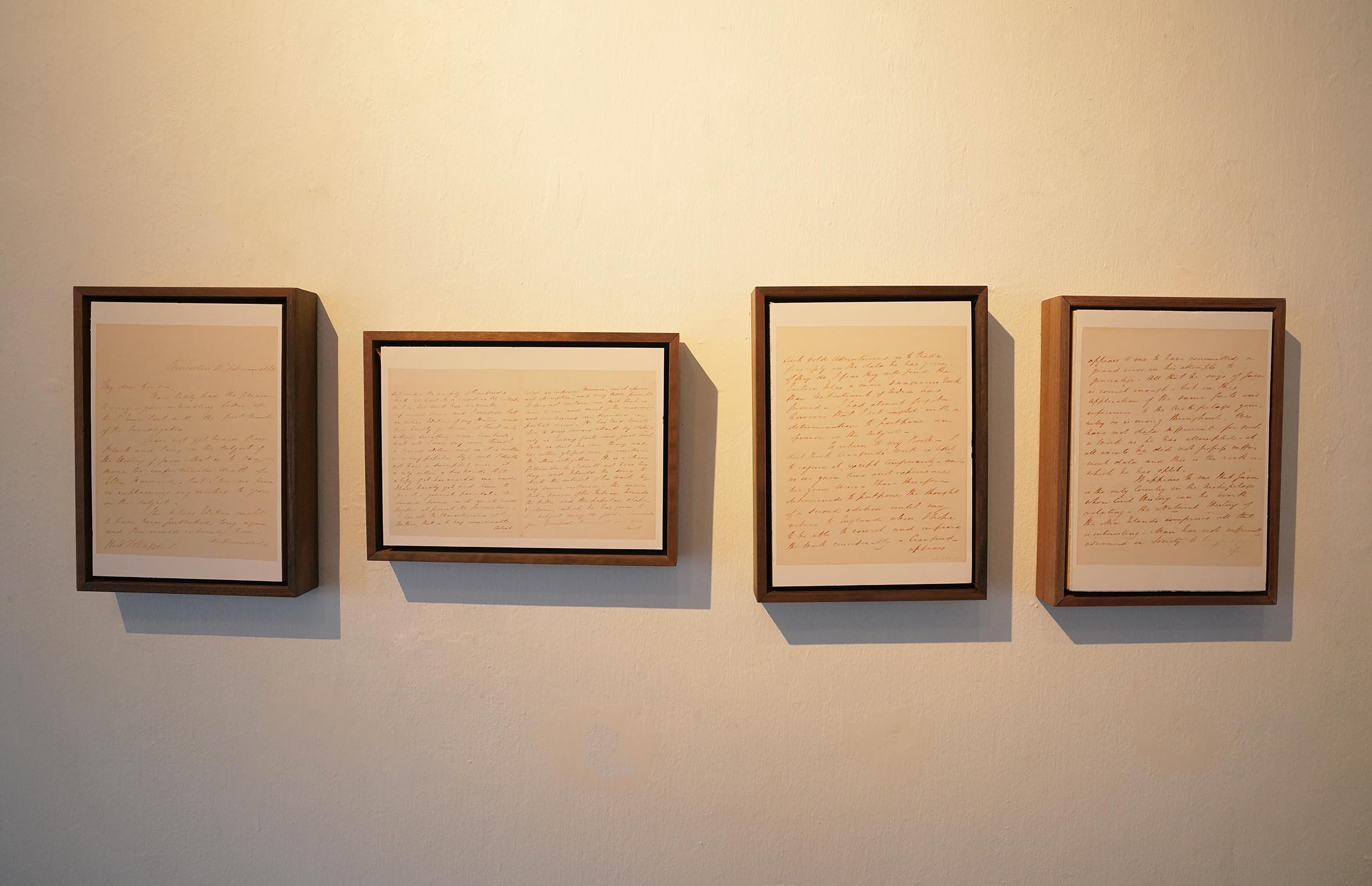

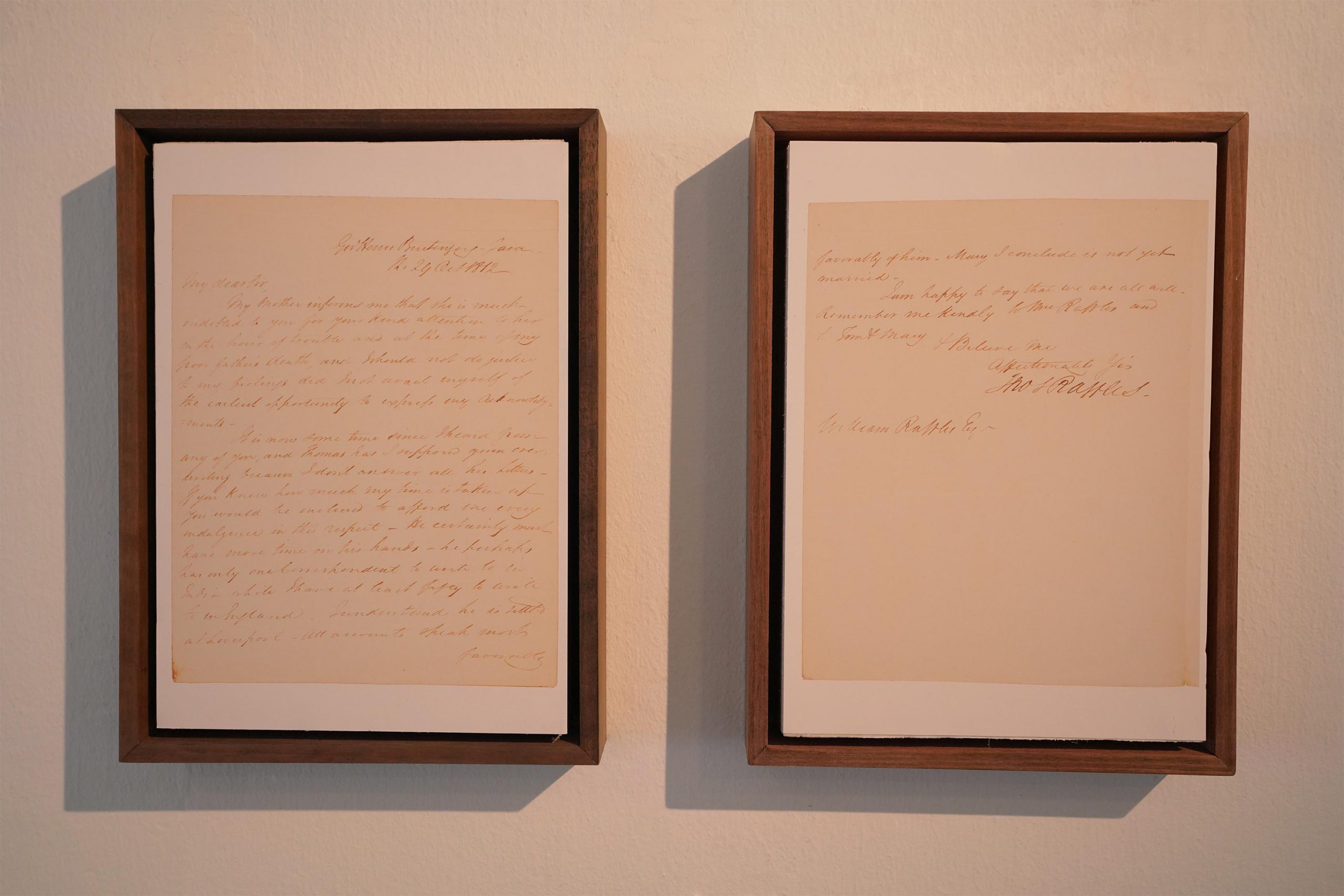

This exhibition is held in tandem with Tang Holding’s gift of Raffles’ personal letters and memorabilia to the National Museum of Singapore, and the opening of the National Museum’s exhibition “An Old New World: From the East Indies to the Founding of Singapore, 1600 – 1819”, supported by the Singapore Bicentennial Office.

This year is the Bicentenary of Stamford Raffles’ arrival in Singapore. Conventionally, the arrival of Raffles (and William Farquhar, later appointed the first Resident of Singapore) is told in a concise manner, lending itself to a general understanding that the history of modern Singapore began in 1819. Much is known about Raffles as an agent of history: we know the Dutch did not like him; we know he fell out with Farquhar and claimed credit for the founding of Singapore. Much of what we know about colonial history, for a long time, has relied on official records from the India and Colonial Offices.

Among the items donated to the National Museum are Raffles’ own copy of his book, History of Java (published 1817). From the beginning, in the Introduction, it is amply clear that the context of Raffles’ recordings are a ‘stock-take’ of the archipel. As has already been pointed out by scholars (most recently in the exhibition Raffles in Southeast Asia at the Asian Civilisations Museum (Jan – April 2019), this documentation of Java, its natural resources, its peoples and culture, is no benign anthropological project: the better one masters the knowledge of the land and its people, the better to master the land itself.

But colonial life was not one homogenous account. Lying beneath the layers of political histories are personal aspirations, dreams, hopes, adventures – sometimes fulfilled, sometimes dashed. An excavation of textual archaeology uncovers the personal longings and stories that provide the foundation of Singapore’s being, and becoming. The Letters and Books of Sir Stamford Raffles reveal the personal affections of Raffles for his intimate circle, a side of him that is rarely portrayed in public accounts of his activities. In a fundamental way, these letters, and their intentions, differ very little from the missives, qiaopi (侨批), jiashu (家书), and other types of letters sent home by those who came from afar.[i] Diaries or chronicles kept by other scribes or sojourners give away the intimate experiences of personal life and thoughts. These materials give us the jiva (Sanskrit: the life force) that humanises our histories, at the same time expresses the jiwang (寄望; longings, aspirations) of actors and sojourners. The linguistic melange in the terms jiva/jiwa/jiwang, and those found in the textual sources, reflect the patterns and dynamics of transplantations and rootedness in our long history.

These textual finds are taken as another point of departure for this proposed joint exhibition by young artists Fyerool Darma and Boedi Widjaja. Together with the location of the exhibition site, 28 Temenggong Road, the ‘ephemeral’ interacts with the ‘physical’, providing the opportunities to interrogate histories and geographies, to uncover the present, and to enquire into the future. Working with the ‘biographical’ (Fyerool) and the ‘autobiographical’ (Boedi) through unseen layers of encoding, the works in this exhibition seek to propose counterpoints with ‘sources’ from alternative origins, to begin to address the imbalance in our approach to historical narratives.

[i] (It may be interesting at this point to also note the coincidence that the origins of Tang Holdings, the donors, trace back to Tan Choon Keng, better known as CK Tang, who was also a migrant who had come to Singapore from Shantow, China in 1923, in search of his fortunes.)

2.

My population on the Island of Java alone, without including the Dependent Territory of the Archipelago – is somewhere about five millions – they are to a man Mahometans – but recently and very imperfectly converted – they still retain many of their Ancient Institutions – (of Hindu origin) but these are gradually giving way to the Koran …

Raffles, Letter (Marked private), Buitenzorg 10th February, 1815

After the Rajah had finished he got up, because no one at down any longer, except the ladies, and I followede my Tuan out of the hall; but I did not hear cannon, nor music, nor acclamations, for the English delight in silence.

An Account of Bengal, and of a Visit to the Government House,

by Ibrahim, the Son of Candu the Merchant (trans. John Leyden)

October 25 1810

One of the items in the donation is a copy of Maria Graham’s Journal of a Residence in India (published 1812). While Raffles’ History of Java was encyclopaedic for the purposes of exploitation, Graham’s Journal was kept for the reader’s “amusement”, as a travel record of sorts. From her “female gaze”, we observe landscapes and peoples described for their exotic aesthetics. She is not unsympathetic to the local population. However she is one with Raffles in the (at least subconscious) belief that by their customs and beliefs, they were inferior to the Europeans. Texts such as hers, along with Raffles’ letters, while of historical value, also represent the cultural advantage colonial records have in being retained and referred to.

Fyerool’s work The Poseur is an artistic enquiry to Graham’s description of Munshi Ibrahim Long Fakir Kandu, whose portrait graces the Journal’s frontispiece: “Ibrahim a Malay Moonshee – From a Native Drawing”. This “native drawing” depicts Munshi Ibrahim in ‘native dress’: yet a ‘native’ Malay might have read the codes of Ibrahim’s dress differently: the pelingkat (the patterned woven Indian cotton) worn by Munshi signals his own identity as a jawi peranakan: his father, ‘Hakim’ Long Fakir Kandu, was a Chulia merchant who came and stayed Kedah before moving to Penang. At the same time, the fashion of his clothes in the style worn in Johor and Riau, held together at the waist by a gilded pending (belt buckle); the inclusion of a ornamental keris as an accessory, and the seal held in one of his hands, signalled him as someone of a slightly higher social standing than the ordinary Malay person – little of which we can learn more simply from the drawing’s caption.

Graham’s journal describes the encounter with Ibrahim (a scribe accompanying Dr John Leyden, the Scottish linguist who travelled and served with the East India Company ) at a reception given by the Maharajah. After the event, Dr John Leyden handed her his translation of Ibrahim’s own reminiscence of the evening: this is dismissed as a ‘caricature’ attributed to Ibrahim’s supposed lack of education in English literary forms. Crucially, we do not have the reference to the original text Ibrahim produced: his words had been mediated for him by Leyden. We will never know if the clumsiness of prose, or the excitability in tone is of his own account, or to Leyden’s translation of Ibrahim’s Malay text – his voice is lost.

As Graham imagines Ibrahim’s removed-voice to be clumsy, The Poseur re-imagines the right of representation back to Ibrahim as a dignified actor, calm, in the video component of the installation. The response to the colonial text is a visual (and contemporised) one. We see “Ibrahim” updated to the present, a screen avatar rotating on his axis in full three-dimensionality, counterproposing the imagined “other” perspective. A voiceover reads out Graham’s reminiscence of the encounter. A screen avatar counterproposes the imagined “other” perspective, inverting the intention (or un-intention) of Graham’s illustration. The actor is, as he was depicted in the illustration, silent: he may have his opinions to his observations of Tuan Leyden or Tuan Raffles: but he is not giving it to us, nor giving us the agency to mediate on his behalf.

3.

Immigrants, whether colonials or sojourners, often manipulate and rearrange a local landscapes to create a familiarity in the environment (thus did the East India Companies bring European architecture, and the Chinese and Indian their pavilions and temple styles, to this region.) In the other direction, exotic objects, when collected from lands beyond, and assembled in a domestic interior, grants the veneer of worldliness and sophistication (for example, in late Victorian drawing rooms adorned with Chinese porcelain, Manila shawls, and Japanned cabinets; but also in the 16th century Javanese poem Bujungga Manik, which we will encounter.) Our collecting decisions, even for historical/heritage reasons, create a ‘market’ for the historical narratives we tell. The Poseur is an installation with a series of components that make reference to the commodification of material culture and its consumption. Fyerool’s installation is interacted with two textile hangings: one with a check-patterned textile that is reminiscent of the pelingkat worn by Munshi Ibrahim, another has as its background a Dutch-style still life image; both are emblazoned with the Chinese decorative motif of flames. Making reference to complicate and interrogate the systems and structures of the commodification of material cultures, these textiles and the image of the Travellers’ Palm as a backdrop to the installation evoke the aesthetics of images on postcards or t-shirts made for the tourist (traveller) market – the collection of which is not a dissimilar practice as colonials collecting the local: to bring a piece of the local home. Albeit more haphazard and random, these snapshots presume a ‘knowledge’ of the local: was Graham’s descriptions in her journal not sometimes thus?

Corresponding to the avatar of “Ibrahim” (who has “life” on screen), is a replica sculpture that is reminiscent of a European sculpture (and perhaps even of Raffles). Graham, in her journal entry of 18 August 1810, writes of her encounter of a Cenotaph to Lord Cornwallis in Madras, “which has cost an immense sum of money, but is not remarkable for good taste;” she is nonetheless pleased to see “public monuments in any shape to great men.” Fyerool’s replica (based on an original in the collection of Temenggong Artist’s in Residence), inverts the monumental convention: in its reproduction it hints at our reproduction of ‘great man’ narratives of histories, how we continue to memorialise major historical actors. The earth deposits and detritus in the resin, taken from the Telok Blangah vicinity near the Temenggong’s compound, leads the viewer to consider: what is the ground (both literal and figurative) upon which the ‘great man’ stands, what has he drawn on and exploited, in order to achieve his stature. Without the soil (and the agency of the people of the land), can the ‘great man’ stand?

My dearest Mother

We have just embarked from Calcutta on our return to the Eastward and it is very uncertain when we have another opportunity of writing, I am anxious to send you a few lines from hence to say we are all well – …

I do not return to Bencoolen direct, but proceed in the first instance to Penang – Our anxiety to get back to Bencoolen is however very great, as we left our little Babe there, and Sophia is now within three months of a second confinement – this at all events must not happen on board Ship – …

Raffles, Calcutta – on board the Nearchus

8 Dec 1818

Many were the people who said: ‘Where are you going my Lord?

Why are you so unexpectedly travelling all alone?’

Thus questioned I did not want to speak.

The Story of Bujangga Manik: a pilgrim’s progress[i]

Colonials, and very often migrants in the colonial period, sojourned, travelled – but seldom stayed. Featuring this trope of movement also is the Sundanese poem Bujungga Manik (dating to the late 15th century – early 16th century), another text that has informed Boedi’s creation in Path 10: A Tree Talks / A Tree Walks. Predating Raffles’ History of Java and his personal letters written from Buitenzorg (Bogor), and later Bencoolen, the epic poem, written originally on palm-leaf, centres on this theme of sojourning and longing.

The protagonist in Bujungga Manik, a Hindu-Sundanese prince from Pajajaran (the capital city of the Sunda Kingdom, located in present-day Bogor), undertakes two journeys of pilgrimage eastwards of Java island. His travels are punctuated by homesickness for his mother (interestingly, like Raffles, the prince grew up absent a father), encounter with coastal travel and travellers of other origins on a ship from Melaka, and the affections of a princess. The poem includes mention of objects from China and other luxury goods from overseas, such as cloth and perfume, reminding us that the fluidity of [material] cultural exchange in the region goes back a long way.

[i] From J Noorduyn and A. Teeuw, Three Old Sundanese Poems, KITLV Press, p.242

5.

These directions of travel implicated by historical figures, and the texts that underpin them, present us with our first layer in Path. 10, a complex series of components that interweave parallels in history. Memory can be transmitted epigenetically through the coding of our genes. From the textual, to the ‘invisible’, the ‘barely visible’, and the encoded, Boedi’s Path. 10 is suggestive of the conscious articulations and subconscious dissonances in the narratives of our histories, personal or shared.

The Javanese sea and archipelago, and its ensuing cultural connections, calls out to the site of 28 Temenggong. The project begins with an outdoor live art installation sited in the lower grounds, laid out directionally as the umpak of a Javanese sakaguruwould need to be. The cardinal directions of travel also evoke the pilgrimage of Bujungga Manik’s prince, the migration of Boedi’s grandfather westwards from China to Surakarta, Java, then Boedi’s own journey across the straits to Singapore. As the umpak is fundamental to the stability of a building, this work ‘grounds’ the series. Signalling the use of codes (as well as making reference to maritime navigation) to convey the artworks are three flags encoded in Morse, “A Tree (T)(W)alks”.

The trees that walk and talk in Path. 10 make reference to the names of grandfather Wutong, namesake of the Chinese parasol tree, Firmiana Simplex, and Boedi’s namesake, the Bodhi Tree. For the project, Boedi, in collaboration with geneticist Dr. Eric Yap, has grafted Y-STR marker DYS389ii from his Y chromosome (which transmits his patrilineal genes), joined at two ends by a sequenced fragment of the DNA of the F. Simplex, creating an artificial DNA-sequence. Using this created strand, Boedi introduces injects/elevates the sense of the historical into the personal, and the personal into the historical. This strand is bookended by an encoded text that reads “梧桐语 ·菩提径” (wutong yu, puti jing; The Wutong speaks; the Bodhi-tree takes his path: ergo, “A Tree (T)(W)alks”.) The invisibility of the created DNA strand in turn is a symbol of the unseen inheritances within us, that find expression in our physical appearances and actions.

How is the text encoded? The genetic code consists of 64 triplets of neucleotides, called codons. With the exception of three, these codons encode the synthesis of proteins for 20 amino acids – similarly, after the vowels of the Javanese hana carakaorthography is removed, twenty is the number of consonants remaining. In an act of intergenerational intervention, the artists’ father reads the six Chinese words in his Indonesian-Chinese pronunciation, providing us with the consonants required. The encoded text is created by mapping the consonants of the Javanese script to the codons (the 3 nucleotides that write the amino acids) to from part of the artificial DNA sequence.

The earth excavated from the grounds is placed at the foot of the flag. The DNA sequence created by Boedi is suspended in a solution of ink. In an act of intervention, the audience is invited to pour this solution over the mound of earth: symbolically returning the [human] ‘trees’ to their roots. A microcosm of this DNA-infused earth is then ‘domesticated’ in a petri dish, displayed indoors, adjacent to a mounted triptych iteration of the flags from outdoors. In the background, we hear the articulations of Wutong, mediated through the voice of Boedi’s father. Path. 10 then begins to ‘expand’ under a microscope: evoking the process of a single-letter mutation found in DNA, the project title (implicit with the identities of the two ‘trees’ Wutong and Boedi) is captured on a microdot. Infused in a solution of the same DNA, the single letter variance between “Walk” and “Talk” in the microdot evokes a single-letter mutation in DNA.

The Bujungga Manik and Raffles’ body of letters and publication provide a testament to the historical. The final work in Path. 10interweaves pre-colonial, colonial and personal histories by presenting a fragment of Wutong’s letters grafted with the Bujungga Manik in coded calligraphic form. Boedi creates a continuous inked surface, incorporating the number of nucleotides (64) with the same number of hexagrams in the yijing. This final expression embodies the personal encodings under the skin, and at the same time, returns Path. 10 to where the series began: in the boxed lines excavated outdoors, on the grounds of 28 Temenggong.

6.

Our space, our geographical location, predates the arrival of Raffles. Before the development of the bungalows and high-rises that we encounter today, this space had a context. The sea defies demarcation. Its openness, its fluidity, provides estuaries for slippages and exchange that are constantly moving, resistant to attempts that seek to restrain it. While 28 Temenggong Road is taken as a site of exhibition, it also offers much potential as a site of enquiry. Facing historic waterways that connect us to the region and the world, named after a historical relocation of the Temenggong, becoming the residential quarters of naval officers, sited near a former shinto shrine on Mount Faber — the stones and earth of the site carry the vestiges of the past.

Chang Yueh Siang

Curator